Houses & Mortgages: UK

Are you better off buying a house or renting one?

There is a mathematical answer- and it all depends on your personal situation. Find out for sure here

Things have changed a lot in the last few years. Will you be better off buying or renting? There are so many variables that to answer this question properly needs some work.

We have built a comprehensive analysis tool to walk through all the maths and work out if you’re better buying or renting.

Step 1: get the details of a house you’d consider buying, and the same for an equivalent rental option.

Step 2: click the button below to use our free calculator, input the information for both your purchase and rental options, plus your own variables and see for sure which is better for you.

UK Houses; a good investment?

Know your risk before you buy a home.

Most people in the UK will tell you a house is an asset. Some finance gurus like Robert Kiyosaki will tell you it’s a liability.

Without doubt, those who’ve owned property in the UK over the last 20+yrs have done extremely well.

UK houses have been one of the best performing asset classes for most people in the UK. Anyone over the age of 50 has likely made far more in their house than any other investment they’ve ever made. Given the average holding period is around 20 years, most people will have seen their properties increase in value by between 3-8x (depending on where they live).

Add in the fact that property is an investment that most people lever up to purchase (ie they borrow money) and the cash on cash return for people is even greater.

House prices today stand at an average of 9x annual income. In 1970 they were on average 4x income. That significant real change in the price of homes has had a huge impact on society, the wealth dispersion across age groups and overall living standards in the UK.

Is a house a good investment today?

When considering buying a house to live in, there is a significant emotional element to consider- owning your own home brings a sense of peace and security which should not be ignored. It is not purely a financial decision.

However, for simplicity what follows here is a purely financial assessment of the risk/return of buying a home to live in. (Buying property to rent is a different calculation).

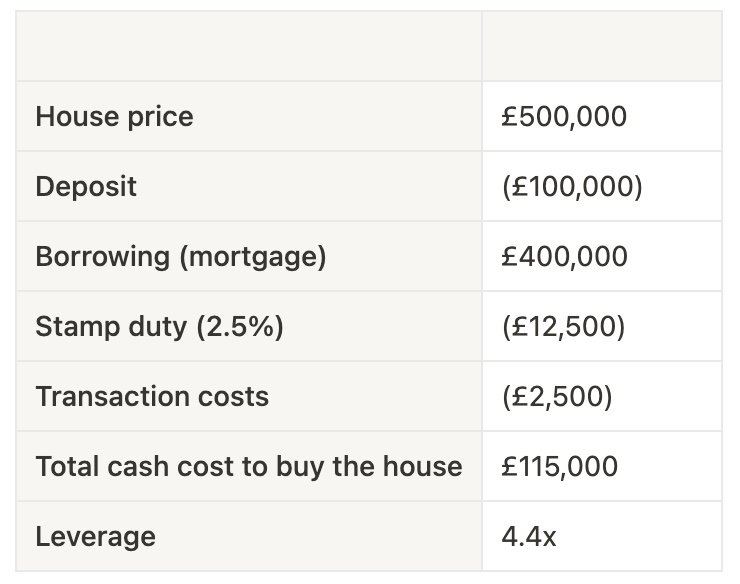

Let’s work through a simple example assuming a £500,000 house with a typical 20% deposit.

These are the approximate purchase costs:

I mentioned briefly above the leverage involved with home buying- you can see here that you’ve increased your buying power 4.4x by using a mortgage- that’s your leverage.

Side note: its an interesting societal quirk that we’re happy accepting huge amounts of leverage on houses- but if you approached someone and suggested they take out a loan of 4-5x their annual salary to invest in anything else (stocks, gold, savings, a business etc) they’d certainly tell you you’re crazy. When it comes to houses we see that debt level as absolutely fine, and indeed recommend it.

We’ll work through some scenarios to see what will happen if house prices go up or down after you buy that house.

Scenario 1: house prices rise 10%

If the price of your house rises 10%, this is your return (including 1.5% transaction costs to sell, which you’d need to pay to actually get this return).

Note- all of these calculations ignore the impact of mortgage paydown (you paying your mortgage every month) for two main reasons:

1. it makes a tiny difference over any time period of less than 10 years,

2. paying down the mortgage uses your own money, so it’s not an investment return.

The 10% price increase has created a 23% return (thanks to your 4x leverage). That is brilliant. But, if you sell your house you need to buy another one to live in.

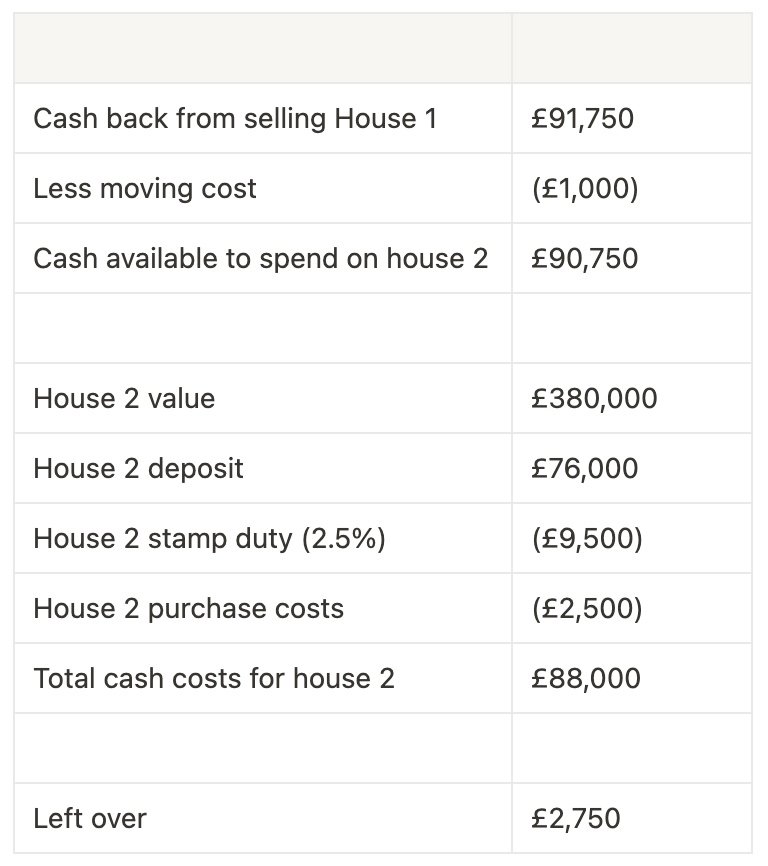

Assuming you aim for the same value and don’t trade up or down, you will need to sell your current house, buy a new one, plus physically move. The total transaction costs involved in moving house are pretty significant:

Transaction costs are around 7-8% of the total value of the property. Many people won’t think of the stamp duty they paid for house 1- but that’s real cash that you can’t get back so it’s a legitimate part of the overall transaction costs that needs to be considered.

This is what it would look like to move to house 2:

Counting in the real costs if you want to move your actual return on a 10% price rise is now a 7% profit. Seems fine, but you can see that the transaction costs have eaten some of your profit.

Scenario 2: prices stay flat

Let’s assume you’ve been in your house for a while, the price hasn’t moved at all but you need/want to move.

This is what it looks like for you:

Flat house prices will leave you £24,250 short of being able to move to an equivalent house- you’ll lose £23,250 of the £115,000 you originally put into the first house.

You’ve now only got £91,750 to put into buying a house, quite a bit less than your first purchase. So you’ll now only be able to afford a cheaper house- this means your buying power has been eroded. But by how much?

Unfortunately, it’s a lot. Flat house prices will erode your real buying power by around 24%. You will now only be able to a afford a house priced around £380,000:

If the value of your house doesn’t go up, you will lose almost a quarter of your buying power.

And what if things got worse and prices actually fall?

Scenario 3: prices fall 10%

Rather than flat prices, if instead prices fall you’re going to be in real trouble.

This is where leverage hurts- it’s great on the upside and really painful on the down.

You’ve just lost £73,250 of your original £115,000 investment for just a 10% price fall.

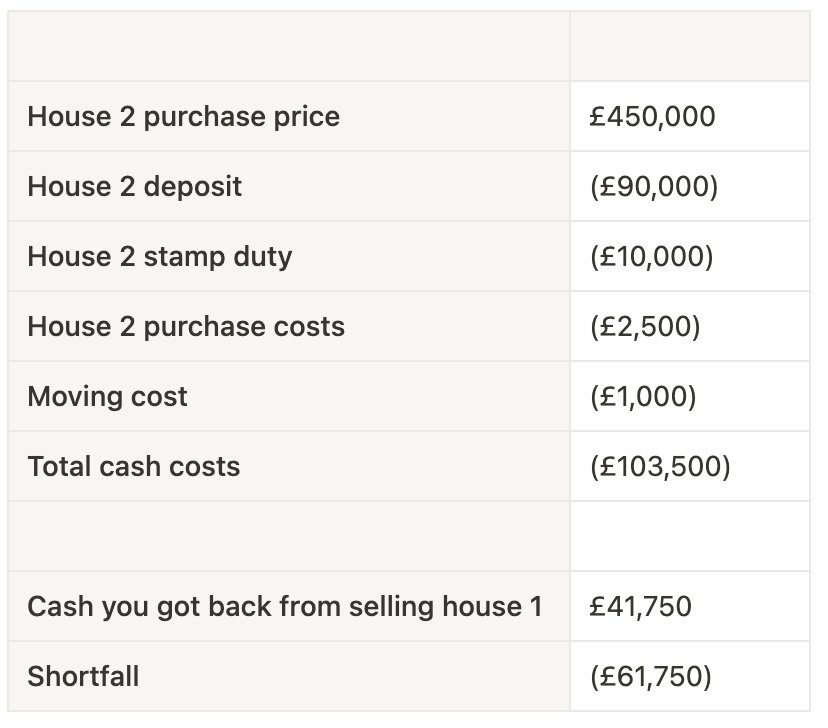

But that’s not even the nasty part… the real problems come when you try to buy another house.

For an equivalent house you’re going to need a deposit of £90,000 (lower than before as prices are down 10%), plus the usual stamp duty and solicitors and moving fees.

Your total cash requirement is £103,500 (down from the £115,000 you needed first time round):

You’re now £61,750 short of being able to buy an equivalently priced house somewhere else.

If you don’t have an extra £61,750 to put into a new house, you’re going to have to downgrade. Using the same 20% deposit requirement your £41,750 you’d get back from selling House 1 would now buy you another house priced at only £208,750.

Just a 10% decline in the price of your house more than halves your buying power.

Return vs Risk Summary

Here are the summarised returns from the above scenarios starting with a £500,000 house:

Buying a house is not an even bet- your downside is more than double your potential upside.

This is what happens when you apply huge leverage to an asset with high transaction costs.

What does all this mean?

It means you need house prices to keep going up. They can’t fall or even just stay flat.

If you think house prices will continue to rise, then you should buy one as you get levered upside return. You’ll have greater buying power and be able to move to a nicer house in a few years time as your buying power will increase faster than the house prices.

But unless the price of your house goes up, you stand to lose a lot of money.

If house prices stay flat, you’ll lose almost a quarter of your buying power.

If house prices fall 10%, you’ll lose more than half of your buying power.

If either of the above happens, you have three options:

stay in the house and hope the price goes up

stay in the house and wait until you’ve either saved sufficient additional cash to maintain your buying power or paid that much off your mortgage (likely 10+ years)

downgrade to a less expensive house

In reality most people will choose 1 or 2. They will be forced to stay and not be able to move.

If you’re worried that prices may fall or even just stay flat, you need to very carefully consider the financial risk you’re taking on when buying a house, and expect that you may be forced to stay there for at least 10 years.

Should you consider renting instead for a while?

Despite the societal negativity and social pressures against renting, it can work out as more cost effective depending on your situation.

To understand which is best for you, use our free Buy vs Rent Calculator- click here.

Should you overpay your mortgage?

A financial analysis of the costs/benefits.

Mortgage rates have gone up a lot in recent years, so many of us are now overpaying our mortgages to reduce the overall balance and monthly payments.

Is this a good idea? Mostly not. For most of us, if your goal is maximising your personal wealth, then overpaying your mortgage will be a negative. (note the goal of ‘maximising your personal wealth’- is a purely financial goal and doesn’t account for the psychological benefit that people get from having little or no mortgage).

Why is it probably not a good idea? Because a mortgage is the cheapest form of money any of us will probably ever get (for more background on why the ‘cost of money’ is different for mortgages, savings, investments etc, click here).

For each of us, our overall financial position is a direct result of how much money we either have outright, or have access to. So paying back the cheapest source of money you can get is typically not the best way to maximise your wealth.

Step 1: Pay other debts first

First things first, before you even think about overpaying your mortgage, the best place to start is probably to make sure you’ve paid off your other interest bearing debts. You want to reduce the expensive debts before you remove the cheap ones. Personal loan, credit card, car finance etc- all will have a higher interest rate than a mortgage and so need to be removed first.

Once all the other debt is gone, and you’re now considering paying down your mortgage, your next question (as with any financial decision) should be one of opportunity cost: ‘what else could I do with this extra money I’m considering overpaying my mortgage with?’

Here we get into the meat of it, and find that there are two main problems with overpaying your mortgage:

Problem #1: Flexibility

One of the biggest unseen costs of paying down your mortgage is that you lose access to your own money. If you overpay your mortgage by £500 a month for 3 years, that’s a total of £18,000 that you’ve saved, but also locked away somewhere you can’t access it.

It’s your money (you earned it, paid taxes on it), but you now can’t get at it. You can’t withdraw it if you need it for an emergency, you can’t move it somewhere else if you get the opportunity so save/invest somewhere else to earn a higher return. The only way to access your own money now is to do a remortgage or an equity release- at which point you’re now going to have to pay interest just to get access to your own money!

Problem #2: The maths

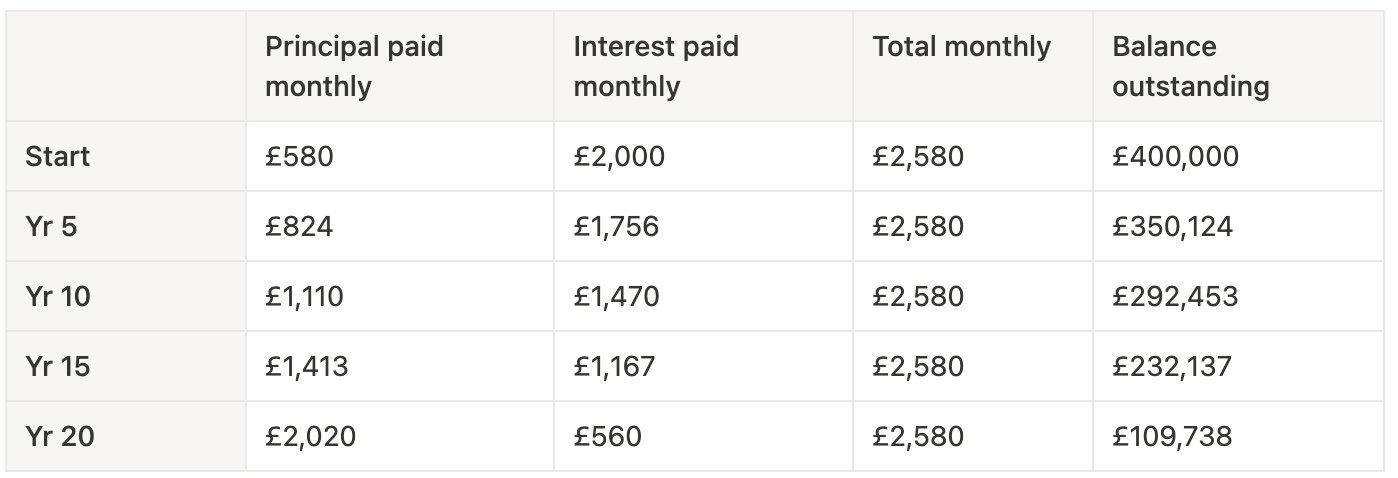

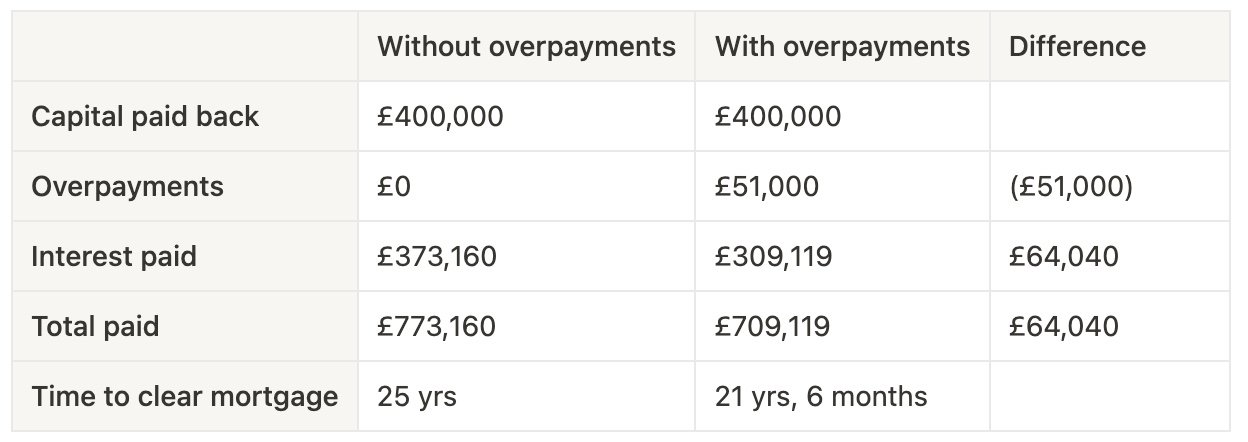

If you take out a £400,000 25 yr mortgage at around 4-5% (and assume for simplicity rates stay the same of the mortgage), your payments will look something like this:

In year one, around two thirds of your payments goes to just paying interest. By year 20, two thirds of your monthly payment goes towards your principal.

Let’s say you are considering overpaying your mortgage by £200 a month to shorten your mortgage. When you add up all those extra £200’s, they total £51,000 by the time you clear your mortgage. This is the impact:

So over paying by £200 a month you’ve shortened your mortgage by around 3 and a half years, and saved yourself around £64,000 in interest. That’s a significant amount.

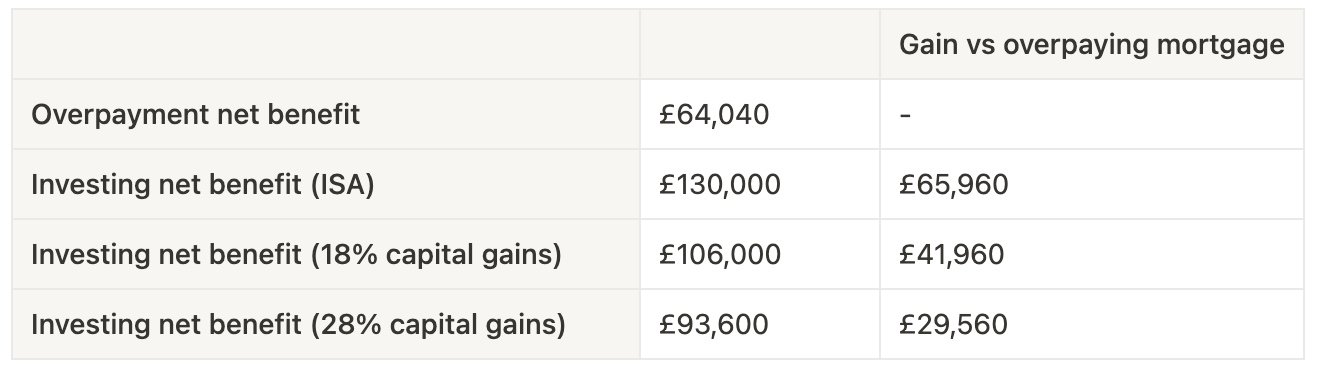

But what else could you do with that same £200 a month? For a very simple comparison, assume you invested £200 in a stock index tracker, which have averaged 8-10% a year over a very long time.

After the same 21 yrs, your investment pot would’ve grown to somewhere in the region of £130,000-£170,000. Let’s use the £130,000 to be conservative. If do this in an ISA, there will be no income or capital gains tax to pay (same as on the house if it’s your primary residence).

Even if you’re maxing out your ISA allowance elsewhere and you simply make these investments in a normal taxable investment account, after tax you’re looking at £93,600 if you’re paying 28% capital gains, or £106,000 at 18%. The overall comparison is:

In every scenario your financial situation is far better if you invest vs overpay your mortgage. If you can do it tax free in an ISA you’re going to find yourself £65,960 better off compared to overpaying on your mortgage.

Plus, you’ve had complete access to that money the entire time should you ever need it. Being able access these funds in case of an emergency (or perhaps just a better saving/invest opportunity) is hugely valuable.

What if you’re older and have only got a few years to run on your mortgage?

In this scenario, overpaying may make sense as you might not want to take investment risk on your money. If that’s the case for you- compare your potential interest rates on savings products to your mortgage rate. If you can’t generate more on your money than you’re still being charged on your mortgage, then it can make sense financially to overpay or clear your mortgage entirely.

Why is overpaying so popular when for most of us it doesn’t make financial sense?

There are a few main reasons:

Most of us don’t know how much better off we’d be by doing something different.

Psychologically people want to remove their debt, so would rather do that than invest.

People don’t consider the cost associated with losing access to their own money.

The investment returns aren’t guaranteed- you may do worse or better than above.

Many people know they don’t have the discipline to keep saving consistently for a long period, but bundling it into a mortgage makes it easier as that money is locked away from them.

That final point is an interesting one and creates a significant benefit for many people by enforcing discipline. Without doubt locking your own money away and having to pay interest if you ever want it back is illogical, but for many of us it can have a benefit in terms of enforcing discipline. There are times when even the most disciplined among us might find it too easy to dip into pots of money if they’re easily accessible. Do that a few times over the years and your excess returns will deplete and you may have been better off paying your mortgage down overall anyway.

This is an important consideration, and is why the decision to overpay or not is ultimately very personal. If you are confident in your ability to create a plan and stick to it, you’ll probably be better off financially by not overpaying your mortgage. Placing the savings/investments in accounts like ISAs where there’s a disincentive to withdraw can help to create some discipline and controls.